What most of us recognize as a classic pear is the European pear (Pyrus communis), cultivated since the Bronze Age—the Botticelli form, Audrey Hepburn neck, and colors ranging from eye-popping chartreuse to jewel-toned maroons and golds. The buttery quality that we equate with many European varieties can be credited to Belgians who carefully bred them in the 18th century to give us the names that ring out like guests to Napoleon’s coronation: Comice, D’Anjou, Concorde, Bosc, and Abate Fetel, to name a few. Pears later immigrated to America with great success and the evolution of our own lovelies such as Harrow Delight, Packham’s Triumph, Blake’s Pride, and the mighty little Seckel pear, born and bred in Philly.

What most of us recognize as a classic pear is the European pear (Pyrus communis), cultivated since the Bronze Age—the Botticelli form, Audrey Hepburn neck, and colors ranging from eye-popping chartreuse to jewel-toned maroons and golds. The buttery quality that we equate with many European varieties can be credited to Belgians who carefully bred them in the 18th century to give us the names that ring out like guests to Napoleon’s coronation: Comice, D’Anjou, Concorde, Bosc, and Abate Fetel, to name a few. Pears later immigrated to America with great success and the evolution of our own lovelies such as Harrow Delight, Packham’s Triumph, Blake’s Pride, and the mighty little Seckel pear, born and bred in Philly.

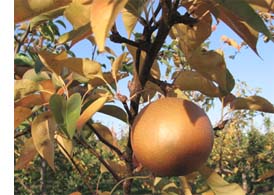

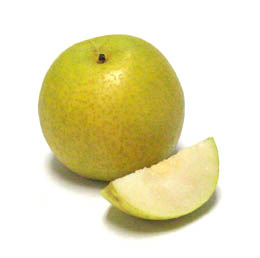

But what of the Asian pear? It presents more like an apple, hence its nickname, the Asian apple pear. But it is not a hybrid of an apple and a pear, but rather another branch of the pear family. Asian pears come mainly from China and Japan where they have a 3,000-year history and derive from the sister Pyrus pyrifolia or Pyrus ussuriensis. The Japanese varieties tend to be more round and apple-like while the Chinese ones may have a more elongated Western pear look to them. The skin of most Asian pears doesn’t get shiny like apples, but is rather is textured matte green, bronze, or gold color. Underneath their skin, a complexity of tastes: firm and crisp flesh with a surprising array of subtle flavors that intensify closer to the core. These fruit are juicy but very firm, so they travel well. European pears such as the Bartlett have a smoother, mellower taste profile.

The season for Asian pears begins in the heat of August and lasts well into the wool hat part of Fall, with a procession of varieties spilling over each other during those months. The translations of their Chinese and Japanese names reveal a bit about them or refer to a grower or region.

The juicy golden Hosui means “sweet water” in Japanese, according to Holly Harter at Subarashii Kudamono, and the legend they like to share is that Asian pears are the grandfather of all pears (European pears) and they themselves are the grandchildren of roses. The butterscotch-flavored Chojuro is named after the man who hybridized it; the elongated Ya Li means “duck pear” in Chinese. Asian immigrants planted Asian pear trees along the West Coast where they flourished, both under their original names and some new names. The popular 20th Century also goes by Nijisseiki both here and in Japan. On the East Coast Subarashii Asian pear growers have bred their own varieties, naming the fruit after family members with an honorific ending “-san,” such as “Lilysan” and “Elisan.”

One prime component to the enjoyment of both European and Asian pears is their fragrance. Pears are climacteric and will ripen once off the tree. They also ripen from the inside out. To test for ripeness on European pears, check the neck: if the stem yields to pressure, it’s ready to eat. Refrigerate to hold ripeness, but let the pear return to room temperature to best enjoy its flavor and fragrance. Most pears won’t change color, except the Bartlett, which may brighten to yellow. If the 20th Century Asian pear turns from green to yellow it’s a sign to eat it right away. Asian pears keep longer than European ones and can be held in the fridge for a few weeks.

One prime component to the enjoyment of both European and Asian pears is their fragrance. Pears are climacteric and will ripen once off the tree. They also ripen from the inside out. To test for ripeness on European pears, check the neck: if the stem yields to pressure, it’s ready to eat. Refrigerate to hold ripeness, but let the pear return to room temperature to best enjoy its flavor and fragrance. Most pears won’t change color, except the Bartlett, which may brighten to yellow. If the 20th Century Asian pear turns from green to yellow it’s a sign to eat it right away. Asian pears keep longer than European ones and can be held in the fridge for a few weeks.

Want farm-fresh fruit?

We've got you covered.

The pairing of pears and food has long been part of the culinary arts, as well as a favorite of still life painters through the centuries. Fresh European pears match well with cheeses. The sweet and mellow D’Anjou goes well with goat cheese or Brie; Comice with a stronger Stilton or Roquefort; and Bartletts with a Fontina-type. Baked or poached, pears will sweeten ever more and transform into an easy dessert with a bit of maple syrup, honey, or cider.

Asian pear flavors also go well with bright foods and fresh cheese. Combinations could include pecans and almonds, as well as grains like quinoa and millet. Subarashii Kudamono frequently hosts “pearings” in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, featuring top name chefs. Lucy Olson of Gabriel Farm in Sebastopol, CA (Sonoma County), which supplies The FruitGuys with an array of Asian pears, says, “The flavors of Asian pears are more subtle than wine–and without the effects.”

Want fruit for your office?

Get your office a free sample TODAY!

Join the Chief Banana newsletter for weekly fruit facts, workplace wellness ideas, and occasional offers.

"*" indicates required fields

By signing up, you agree to receive emails from The FruitGuys. You can unsubscribe anytime.

Keep exploring.

Browse by theme.

Get easy recurring deliveries for break rooms, micro markets, and more.

Take advantage of faster checkouts and other great benefits.

Create an AccountWe are here to help you provide healthy food, meaning, and a reason to gather in your workplace.

From weekly mixed fruit for break rooms to monthly gifts for remote staff to special projects, we can serve your needs or turn your dreams into a nourishing reality.

Get fruit news, snack tips, and office wellness insights in your inbox each week, fresh from the desk of our CEO (aka Chief Banana)!

"*" indicates required fields