Heroes of Fruit History

- By Kjerstin Johnson

- Reading Time: 4 mins.

When we bite into a crisp fall apple, we generally don’t think about the centuries of cultivation, ongoing scientific development, or countless tiny agricultural advances that put that piece of fruit in our hands. From the lab to the orchard, from the kitchen to the fields, there are many unsung heroes of fruit. Here are profiles of five figures from fruit history who’ve shaped the way we eat, grow, and think about fruit today.

The Preserver: Nicolas Appert

In 1795, Napoleon was expanding his empire across Europe. There was just one problem: food spoiled quickly on long journeys and was going to waste while troops went hungry. The French government offered a prize of 12,000 francs to anyone who could devise a method to preserve perishable food.

In 1795, Napoleon was expanding his empire across Europe. There was just one problem: food spoiled quickly on long journeys and was going to waste while troops went hungry. The French government offered a prize of 12,000 francs to anyone who could devise a method to preserve perishable food.

Guided by homespun kitchen know-how—not any formal training in science—chef Nicolas Appert had long experimented with preservation methods. He had found that when corked correctly and boiled, a sealed glass container of food would keep for several years. Appert won the contest in 1810, and his groundbreaking book The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances for Several Years came out the following year. (The full text is available via Project Gutenberg.)

Appert’s methods are more or less the way canning still works today—and he died a few decades before Louis Pasteur would prove that heat kills bacteria. Today, the Institute of Food Technologists gives an annual Nicolas Appert Award for lifetime achievement in food technology.

The Pollinator: John Chapman

Popular perceptions of Johnny Appleseed—half-man, half-legend—have mostly developed from two sources: a glowing 1871 Harper’s article titled “Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero” and Disney’s 1948 animated movie Melody Time. Both depict Appleseed as a fresh-faced, fruit-loving adventurer. Although they’re not too far from the truth—he had a deep respect for all living things, whether plant or animal, and he did travel by foot with a sack of seeds—they are romanticized versions of the real man, John Chapman.

Popular perceptions of Johnny Appleseed—half-man, half-legend—have mostly developed from two sources: a glowing 1871 Harper’s article titled “Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero” and Disney’s 1948 animated movie Melody Time. Both depict Appleseed as a fresh-faced, fruit-loving adventurer. Although they’re not too far from the truth—he had a deep respect for all living things, whether plant or animal, and he did travel by foot with a sack of seeds—they are romanticized versions of the real man, John Chapman.

Chapman planted more than 800 apple-tree nurseries in present-day Ohio in the early 1800s, but he wasn’t planting apple trees to ensure pioneer kids had nutritious snacks—he was motivated by economics, selling the land to new settlers for a profit. Besides, back then, most apples weren’t for eating at all. The fruits were extremely bitter and sour, unlike the sweet varieties we know today, and mostly used for hard cider, the prairie’s main source of hydration. Before modern water-treatment methods were devised, water could give you a bad case of dysentery—cider would give you a buzz.

Want farm-fresh fruit?

We've got you covered.The Breeder: Luther Burbank

From roughly 1870 until his death in 1926, horticulturist Luther Burbank contributed between 800 and 1,000 plant varieties to American agriculture. He developed more than 200 fruit varieties alone, paying particular attention to plums and berries.

From roughly 1870 until his death in 1926, horticulturist Luther Burbank contributed between 800 and 1,000 plant varieties to American agriculture. He developed more than 200 fruit varieties alone, paying particular attention to plums and berries.

Through propagation, selective breeding, and grafting, Burbank achieved new strains of fruits and vegetables that grew better, yielded more, and tasted amazing. Burbank’s first masterpiece, however, was not a fruit, but a potato. In 1872, he planted 23 spud seeds. He bred the two best seedlings together and dubbed the hardy resulting potato the “Russet-Burbank”—what we know today as the russet potato.

To the dismay of his contemporaries, Burbank’s methods were a bit more art than science: he didn’t keep meticulous records or data. But he was an indisputable genius.

The Artist: Deborah Griscom Passmore

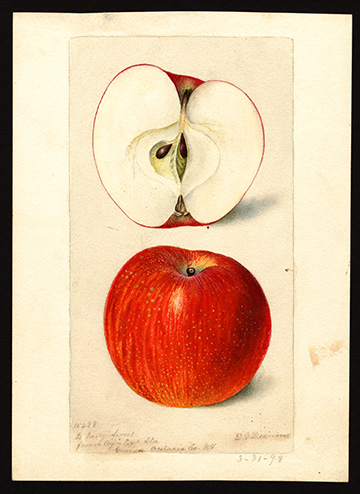

In 1892, the USDA hired 50 painters to document the growing variety of crops across the country, a project that ultimately led to the creation of more than 7,500 gorgeous watercolors of fruits and vegetables. Horticulturists (such as Burbank!) were experimenting with new strains of produce, and because photography was still a nascent and unreliable medium, fine artists were enlisted to capture the images of new species.

In 1892, the USDA hired 50 painters to document the growing variety of crops across the country, a project that ultimately led to the creation of more than 7,500 gorgeous watercolors of fruits and vegetables. Horticulturists (such as Burbank!) were experimenting with new strains of produce, and because photography was still a nascent and unreliable medium, fine artists were enlisted to capture the images of new species.

One painter, however, outshone her colleagues. Deborah Griscom Passmore created one-fifth of all of the paintings and is considered by historians and critics alike the most gifted of the artists. Educated at the Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, she studied under Thomas Moran and was influenced by British biologist/artist Marianne North’s lush botanical works.

Passmore’s watercolor paintings truly blur the lines between art, industry, and science. Her attention to detail, color, texture, and light make her subjects marvels to look at—you can almost taste the flesh of a persimmon or feel the ridges of a Corsican lemon.

Passmore’s renderings were crucial to turn-of-the-century agriculture specialists, and are stunning to viewers today. What’s now known as the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection is available to view online. Once there, you can filter by artist and be captivated by Passmore’s specific contributions.

The Activist: Cesar Chavez

On September 8, 1965, more than a thousand Filipino grape pickers in Delano, California, walked off the fields at noon, demanding better pay. But it wasn’t until a week later, when labor activist Cesar Chavez rallied Mexican-American farmworkers to walk off in solidarity, that the biggest farm strike in American history began. Together, the two groups became the United Farm Workers of America (UFW).

On September 8, 1965, more than a thousand Filipino grape pickers in Delano, California, walked off the fields at noon, demanding better pay. But it wasn’t until a week later, when labor activist Cesar Chavez rallied Mexican-American farmworkers to walk off in solidarity, that the biggest farm strike in American history began. Together, the two groups became the United Farm Workers of America (UFW).

The strike lasted five years. Through boycotts, marches, direct action, and nonviolent resistance, the UFW brought corporate fruit producers to their knees with its insistence on better pay and conditions. The strike politicized grapes, and the UFW emblem—a black Aztec eagle on a white and red background—became a symbol of labor and food justice.

Chavez showed us not only the power of solidarity in the face of oppression but that “ethical food” goes way beyond organic vs. GMO. His chant of “Sí, se puede”—“Yes, we can”—has been a rallying cry for progressive causes ever since.

The next time you take a bite out of an apple, take a moment and think of the scientists, artists, laborers, activists, and big thinkers who made that piece of fruit possible. Then enjoy your apple!

Kjerstin Johnson is a writer and editor who lives in Portland, Oregon.