Subsidizing Big Ag

- By Charlene Oldham

- Reading Time: 5 mins.

Small Farms Left Out of Farm Bill

By Charlene Oldham

When the first “farm bill” was created in the late 1930s to help family farms, horses and hand plows were as common on farms as Model As and mechanized tractors. Today the $300 billion farm bill up for revision in Congress is a complex web of extensions and additions to laws originally designed to help farmers rebound from the Great Depression and Dust Bowl.

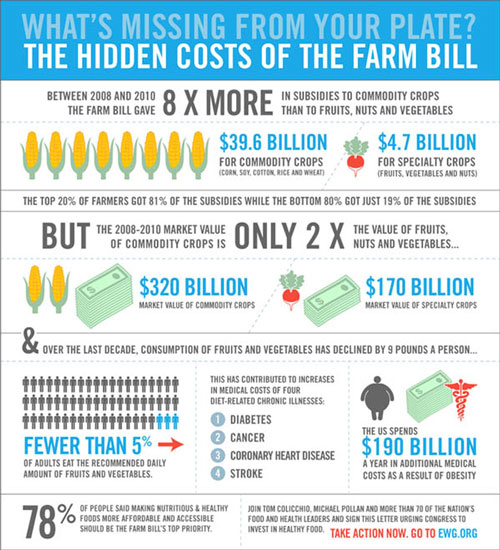

While nearly three-quarters of the bill’s funds now go to food assistance programs for the needy, known as SNAP, it has also become a significant source of subsidies for factory farms and private crop insurance companies. Meanwhile, small independent farms derive few benefits from the modern farm bill, which doesn’t offer affordable crop insurance or price supports for most fruits and vegetables, putting them at a competitive disadvantage with large-scale commodity growers.

What’s more, subsidizing corn, soybeans, wheat, and rice keeps prices artificially low for ingredients, such as high fructose corn syrup and soy oils, later used in unhealthy processed foods.

“The whole idea of the program is to subsidize big growers,” said Jack Kittredge, policy director with the Massachusetts chapter of the Northeast Organic Farming Association. “So we have lots of things in our food supply that are unhealthy because they are cheap calories.”

In 2011, more than $1.28 billion in taxpayer subsidies went to junk food ingredients, bringing the total to $18.2 billion since 1995, according to a report from U.S. Public Interest Research Group (PIRG), a Boston-based public advocacy group. In contrast, only $637 million has gone to subsidies for apples since 1995.

Calling for Reform

A growing number of small farms, interest groups, public health advocates, chefs, and food writers are calling for changes to take the farm bill back to its roots by offering a financial safety net to small farms and giving incentives for growing food crops in ways that promote environmental sustainability and healthy eating.

The farm bill is renewed every five years or so, but this is the first time it expires in an election year. Under the latest versions of the law, which Congress will consider when it returns from recess, the U.S. Department of Agriculture would again provide price supports for some two dozen agricultural commodities, including five crops – corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, and rice – which net the most significant proportion of subsidies in the form of direct payments, counter-cyclical payments, and marketing loan benefits.

Want fruit for your office?

Get your office a free sample TODAY!

Big Farms Get Bigger…

Direct payments, which mostly go to mega producers of corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, and rice, cost the government about $5 billion each year, according to the Congressional Research Service. Direct payments are fixed annual fees based on a farm’s historical plantings and yields, as well as a payment rate set by the government.

Farmers and landowners have almost complete flexibility in what they plant, or whether they plant at all. Indeed, some direct payments have gone to landowners who don’t plant new crops, but live on land that has historically been cultivated, according to the CRS.

Because they aren’t tied to a particular crop price or yield level, these payment rates are often included in land value estimates, making it more expensive for small farmers to buy more acreage or new farmers to get their start. They also encourage large-scale farms to expand their acreage of subsidized commodity crops, crowding out farms that grow food.

“What study after study has shown is that big farms are expanding their holdings at taxpayers’ expense,” said Jack Kittredge of NOFA, who also operates Many Hands Organic Farm with his family in Barre, Mass. “They are driving up the price of farmland so small farmers can’t afford it.”

While some smaller farms do receive commodity program subsidies, 62 percent of U.S. farms did not collect any subsidy payments from 1995 to 2011, and 10 percent of subsidized farms collected 75 percent of all subsidies, according to an Environmental Working Group analysis.

Although current farm bill proposals in both the House and Senate end direct payments, both bills would shift funds to programs that would increase price guarantees and crop insurance subsidies “for the same successful farm businesses that have benefitted from the lion’s share of traditional farm subsidies,” said Sara Sciammacco, director of communications for EWG, a Washington D.C.-based non-profit advocacy group for public health and the environment.

Want fruit for your office?

Get your office a free sample TODAY!

Crop Insurance…

The crop insurance program began in 1938 as a temporary measure to help farmers through the Great Depression, according to a Congressional Research Service report. It still provides some financial security, particularly for farmers who don’t receive agricultural subsidies for commodity crops. But it’s also become a boon for big agribusiness and private insurance companies that sell and service subsidized policies.

In 2011, federal spending on crop insurance subsidies reached $7.4 billion, and the insurance program’s total cost was around $11 billion. Given its price tag, many analysts believe the crop insurance program will soon face the same scrutiny as direct payments.

“I just think it will be at the top of the chopping block,” said Mary Kay Thatcher, senior director for congressional relations at the American Farm Bureau Federation, an independent, non-partisan group representing farms and ranches.

Although the government subsidizes farmers’ premium costs and reimburses insurers for losses and administrative and operating expenses, the insurance policies are sold and administered by for-profit insurance companies and independent agents who work for sales commissions.

In fiscal 2010, those administrative and operating costs added up to $1.4 billion. And, while the federal program recoups some costs in years when premiums exceed loss payments made by insurers, it reimburses insurance companies in bad years, when loss payments outpace premiums. Agricultural economists estimate taxpayers will owe crop insurance companies for an estimated $15 billion in underwriting losses in 2012 when drought has ravaged the Midwest.

Reform needed…

“We hope Congress makes the meaningful reforms to produce a better farm bill that does more to support all family farmers, promote healthier eating, and advance conservation practices,” said Sciammacco, of EWG. “Yet, the 2012 bill is poised to deliver the opposite.”

Sciammacco said the House bill, in particular, presents several problems, including provisions to expand unlimited crop insurance subsidies and increase price guarantees for commodity crops like corn and cotton.

Small farmers and public health advocates agree that giving the bulk of subsidies to commodity crops doesn’t reflect the will of taxpayers, many of whom are increasingly interested in supporting their local farms, sustainable growing practices, and healthy eating habits.

“Those big farms in the Midwest are living off federal subsidies rather than competing in the real market,” said Kittredge, the Massachusetts farmer. “I think if we take those away, we have a much better shot at developing a food policy that reflects what people want.”

EWG, U.S. PIRG, and other advocacy groups encourage concerned consumers to get involved by penning letters to lawmakers and newspaper editors that urge major changes to the farm bill.

___________________

Charlene Oldham is a St. Louis, MO-based journalist.

The FruitGuys Almanac encourages readers to contact their local Congressional representatives and tell them what policies they think the 2012 Farm Bill should promote.